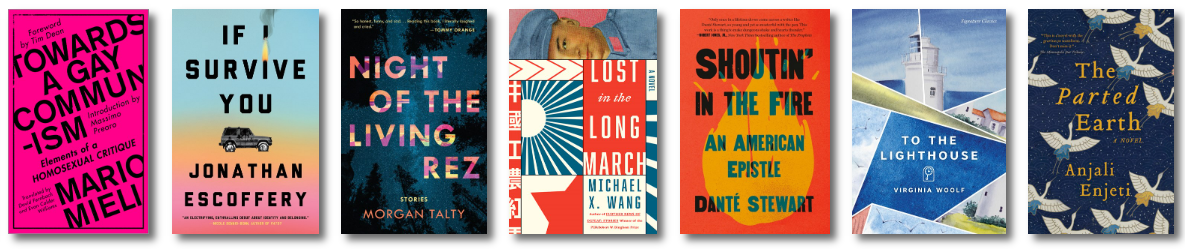

Alejandro Varela is a writer based in New York. His debut novel, The Town of Babylon (2022), was published by Astra House and was a finalist for the National Book Award. His work has appeared in the Point Magazine, Georgia Review, Boston Review, Harper’s, and the Offing, among others outlets. Varela is an editor-at-large of Apogee Journal. His graduate studies were in public health.

Alejandro discusses The People Who Report More Stress, his new collection of interconnected short stories that examines the impact of stress and anxiety on those living on the margins and the ways that—in a society defined by hierarchies—success does not translate to health and happiness.

The People Who Report More Stress is a collection of interconnected stories set in New York that explores racism, sexuality, and the daily anxieties of living in gentrified urban spaces. When did you know that you wanted to write this book? What was the initial spark?

The People Who Report More Stress is a collection of interconnected stories set in New York that explores racism, sexuality, and the daily anxieties of living in gentrified urban spaces. When did you know that you wanted to write this book? What was the initial spark?

Ten years ago, I was teaching public health to graduate students in downtown Brooklyn. Part of the curriculum was an op-ed assignment, where each student had to write an essay in support of a particular public health policy and submit it to newspapers in the tri-state area. At some point it dawned on me that I’d never published an op-ed, so I took a stab. When they were published, I was left feeling self-satisfied, but also skeptical of their effects. I wondered if the steady stream of informed-opinion pieces across the country (and world) were as effective as I'd believed them to be. Was there a swath of the population who might be more receptive to public health ideas if they were weaved into narrative writing? My public health passion has always been the effects of hierarchical stress on society. And no research has been more convincing to me that hierarchies are bad for health than the studies of upwardly mobile people of color who still have poorer health outcomes than their white counterparts. I figured a queer person of color living in a highly gentrified part of NYC, with a professional background in public health research—read: me—had a lot to mine for the purposes of storytelling.

The book returns frequently to a central couple Gus and Eduardo, representing the pair at different moments and in changing times. Why did you choose to structure this work as interconnected short stories? Is there something about this format that you think lends itself better to the story you wanted to tell?

A relationship, like a city or a mind, has the potential to evolve with time—sometimes devolve. This collection explores New York, the psyche of the narrator (often Eduardo), and the love between Eduardo and Gus (and between Carlitos and Brad), all of which are affected by their political backdrops. My hope was to illustrate the ways in which this relationship, like most others, isn’t immune to, and in fact is often shaped by, social forces. Eduardo and Gus have an abiding love that’s bisected by race and class lines. Their ability to communicate and empathize through their differences is the micro example of what society needs at a macro level. “Tenderness is what love looks like in private, and justice is what love looks like in public,” said Cornel West. So many of our societal ills can play out subtly between two people, and I thought of Eduardo and Gus’s relationship as a starting point.

There’s also a dearth of queer love stories in literature. And by that I mean out, proud, mundane, deep, and abiding depictions of gay adults in love and in life. I didn’t want Eduardo and Gus’s relationship to be the plot; I wanted it to be a character in a way, with its own arc.

And as a writing tool, it’s handy to have a mirror for the protagonist. Gus is a character, but he’s also a dimension of Eduardo. He provides depth and understanding.

While The People Who Report More Stress tackles heavy topics (economic injustice, systemic racism, heterosexism), there is a lot of humor to be found in the book. How did you strike a balance that felt right to you?

Humor is the human characteristic I find most appealing. It’s the currency of my most valuable relationships. In other words, I can’t help myself. It finds its way into my writing both intentionally and unintentionally. On the one hand, I employ humor to undercut and to lubricate the weight and unwieldy nature of the themes in the book. But the very neurotic nature of my characters, who worry obsessively about the injustice around them and their own complicity, can be humorous. I wish I could say the spiralling anxieties are fabrications, but in fact, I believe they represent the portion of our population who is effectively conversing with themselves. People who have been socialized to observe, worry, and be prepared for defense. This alchemy is what leads to the humorous interiority of my narrators.

Was there any part of the book, as you wrote it, that surprised you?

Whenever I accidentally arrive at truths neatly, I’m pleasantly surprised. For example, there’s a realization at the end of the final story in the book, the title story. I wrote it in late 2016. I didn’t know then it was going to be the last story of the collection. I didn’t know if there was going to be a collection at all. But the narrator's realizations in the final moments encapsulate the push-pull of stressors and buffers that I was trying to illustrate throughout the collection. As he stares out that restaurant crowd, just before he attempts to hail a cab, we see how success doesn’t translate to health or happiness in a society defined by hierarchies.

What are you proudest of within the book?

Being able to experiment with form and voice, while still adhering to the same themes and setting, as well as to many of the same characters, was a personal achievement for me. I’ve been afraid of writing in the third person, something about it felt outside of my skill set, which of course made me feel inadequate as a writer. The three stories I wrote in the third person (in addition to one in second person and one without a narrator) allowed me to break away from my reliance on the narrator’s interiority and it gave me vantage points I wouldn’t have otherwise had.

What do you hope readers will take away from The People Who Report More Stress?

First and foremost, I want readers of my work to have a good time. I want them to feel that they invested in something entertaining and hopefully enlightening. I’d also like to confirm their suspicion that climbing the socioeconomic ladder isn’t good for individual or our collective health.

Have you read anything recently that you really enjoyed? Are there upcoming books that you are looking forward to?

In the last few months, I’ve enjoyed To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf, Outline by Rachel Cusk, A Woman's Story by Annie Ernaux, Birdcatcher by Gayl Jones, Latin Moon in Manhattan by Jaime Manrique, and Bless Me, Ultima by Rudolfo Anaya. Next up are Nobody’s Magic by Destiny O. Birdsong, None but the Righteous by Chantal James, Chrome Valley by Mahogany L. Brown, Ghost in Black Girl’s Throat by Khalisa Rae, Towards a Gay Communism by Mario Mieli, If I Survive You by Jonathan Escoffery, Night of the Living Rez by Morgan Talty, Lost in the Long March by Michael X. Wang, Shoutin’ in the Fire by Danté Stewart, and The Parted Earth by Anjali Enjeti.